Depression lies. Deep, dark, dirty lies. Lies that we know are lies. They echo the black places in our hearts that say we don’t deserve better, so we believe it because we need a reason to feel the way we do. We know it isn’t right, but we can’t make sense of anything else. Depression is the ultimate abuser – convincing you that no one understands you like it does. It makes you feel safe, in a bad way, then hurts you again. And this is how we drown.

The absolute worst thing you can say to a depressed person is “Cheer up!”

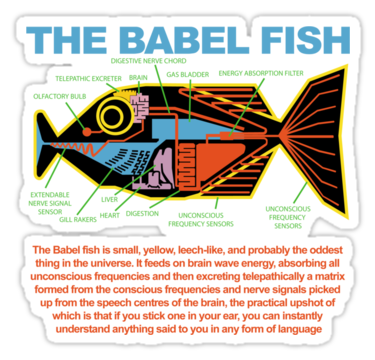

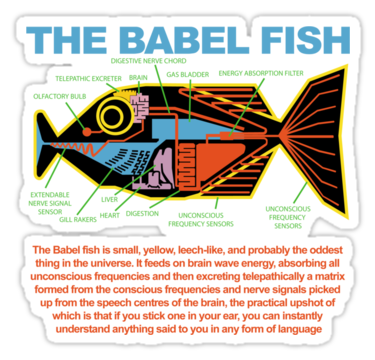

If you’ve never been depressed, first try to wrap your mind around the Babel Fish from Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: A tiny yellow fish that wiggles into your ear and helpfully translates for you. Depression is much the same. However, the depression Babel Fish consistently mis-translates and is pretty much the worst thing you could put in your ear. But it’s not like you had much choice. You’re the host for an alien parasite that takes over your brain – it takes in everything around you and translates it into an inner dialogue rife with self loathing and impotent rage – good, bad, indifferent, everything is twisted into a new language. Every angry thought you’ve ever had turns inward and fizzles out until it all becomes your fault. Far from being the “oddest thing in the universe“, depression is painfully common and just as painfully misunderstood.

Your friend jokingly nudges you to smile and all you hear is that you’re a failure for not physically being able to make yourself force a grin or even feel like you should. What comes through the Babel Fish sounds more like, “Your unhappiness is making me uncomfortable and you’re a bad friend for doing that to me.”

Other people’s feelings are often incredibly uncomfortable, especially when we don’t know how to “fix it”. So we put our feet in our mouths. We do genuinely want them to be happy. Being happy is awesome. I’m told it’s pretty much the best thing ever. There’s puppies and rainbows and salt water taffy. But sometimes it isn’t that simple. No amount of hyperbole can make you better. And depression is so subjective. Everyone suffers in their own personal, isolated hell. One person’s experience and solution may not even register to someone else. We all break differently.

What we need to hear: ”I’m here. I love you. I’ll sit next to you until you can feel like yourself again.” We need empathy over sympathy.

Our culture marginalizes and vilifies mental illness, even one as “mild” as depression. Because others can’t see an issue, we assume the people around us are mentally able-bodied as well as physically able-bodied. Most people wouldn’t think of going up to someone on crutches and tell them to “walk it off” but we don’t hesitate to say “cheer up” when we suspect someone else’s sadness is deeper than we’re equipped to handle. It reinforces the Babel Fish’s mantra – you’re broken and shameful and you should hide. We don’t want to be broken and awkward. So we push it further down and it eats at our insides.

Depression for introverts is especially hard. As an introvert, the idea of going out in social situations can be overwhelming. Thinking about being around that many people (even if you adore them) is draining. Coupled with depression, being social ends up being absolutely crippling. If you manage to make it out of your house, more internal effort is spent trying to mimic the appropriate level of enthusiasm or focus than on registering anything around you. More often than not, depression drives introverts even further into themselves. Down a rabbit hole of radio silence and missed appointments.

Slogging your way through requires a massive amount of deprogramming. It exacerbates any other anxiety, issue, or disorder. Every day is an effort in un-brainwashing yourself simply to function.

We set small goals: “I will get out of bed today.” “I will not wear this hoodie for more than a week at a time.” “I will make an effort to be presentable.” We recognize our minuscule victories when we attain them.

We acknowledge and identify moments when we actually think or feel something. Especially something positive: “I’m actually kind of happy right now.” “I really needed that hug, thank you.” “I don’t completely hate how I look today.” Like the first, tentative, pale green shoots of Spring. We’re so battered by feeling negative things, we’re scared to open ourselves up to feeling anything at all.

Sometimes, we medicate. Either with pills from the doctor that modify how our brain works (or isn’t working, as the case may be) or with diet and exercise – those old standbys. Or some combination of all of the above. Sometimes we’re less constructive and the Babel Fish convinces us that one more shot of whiskey will totally help. It doesn’t.

More days than not, we feel like Sisyphus. But eventually the days between being smacked back to your starting point become longer. If you are very lucky, you find your way on the other side and you’ve figured out how to evict the Babel Fish. Many of us, however, have to learn how to live with the Babel Fish. But we can make it more of a tenant rather than a parasite.

We know it’s there. Those who love us know it’s there. Lurking. Waiting to catch us when we’re vulnerable.

And our friends sit next to us when the Babel Fish is being a particularly ungracious tenant and tell us, “I’m here. I love you. I’ll sit next to you until you can feel like yourself again.” And we are very, very lucky indeed.